Ireland prepares to surprise itself in the 2016 election to its Dail (parliament) on 26th February — an election in which, like elsewhere in Europe, smaller parties are expected to gain votes.

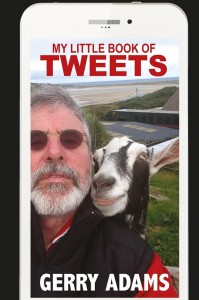

Sinn Fein can no longer be described as one of the smaller parties. It expects to significantly increase its presence.

But some who wanted to make this the worst possible campaign for Sinn Fein’s leader Gerry Adams, who led his party into the peace process that ended 30 years of armed conflict in Northern Ireland.

On the English side of the Irish Sea there was a bit of bilious talk: the man was a scumbag who covered up sexual abuse by his brother Liam when he first learned of it in 1987.

It was then that his niece told him of his brother’s sexual abuse, and it was then that he discovered how his father, a well-known Republican campaigner, had abused some of his own 10 children.

More than a decade later Adams made a remarkable television announcement exposing his father and explaining the devastation wrought in his large extended family.

“I was almost 50,” he said when he learned of the abuse, “everybody was coming at this at different speeds and from different perspectives.”

He’d always wanted to go public — he was, after all, a globally iconic figure and a person allowed few private confidences.

Finally his brother Liam Adams was jailed for 16 years last year after losing an appeal against his conviction.

Gerry Adams isn’t a scumbag, and he didn’t cover it up, he tried to manage it.

What we know about child sexual abuse is that it blows families and people apart.

This side of the Irish Sea it is easy to hate the IRA and Sinn Fein — the Establishment has waged war on Republicanism, after all, forever.

You don’t have to be a Republican yourself to know that all of our engagements with its politics have to be mindful of that history, and our place in it.

Even Adams’ enemies acknowledge that he is a dignified, discreet, strategic — though, of course, imperfect — political leader who helped get his movement out of the mire into the political light.

Of course, there is dirt in his story — it was a very dirty war.

He didn’t cover up the abuse, he acknowledged it; when his niece Aine told him in 1987, he tried to manage it. He may not have managed it very well.

In England in 1987 the government launched the first and longest public inquiry into sexual abuse in Cleveland, a county in the north east of England.

We are talking about 1987, who addressed sexual abuse well?

Of course he made mistakes. However, he didn’t cover it up he tried to manage it.

What seems to have happened is that he confronted his brother; Liam was sent over the border to Dundalk — hiding place of many Republicans, where no doubt it was felt that people would keep an eye on him.

In 1987, lest we forget, how many people knew that a man who abused his own daughter would be capable of abusing other children, boys and girls?

In 1987 it was inconceivable that Adams could have gone to the police in Belfast.

Adams had already survived attempts on his life; the British were fiercely resisting an equality agenda — the MacBride Principles — initiated by human rights and feminist activists as a way through the political impasse.

The paramilitary organisations were trying to come up with a peace plan in the mid-1980s. But in 1987 the British sent Brian Nelson, an agent in the Orange/loyalist UDA to South Africa to acquire an arms cache that was then distributed among the loyalist paramilitary organisations.

The British — MI5 and the Army — re-tooled and modernised the intelligence delivered to the UDA so that it could more effectively target Republicans. We are talking about death squads.

In 1989 they killed the human rights lawyer Pat Finucane.

If you don’t believe me, check out John Ware’s Panorama programmes on Brian Nelson and the death squads and the British security services; check out British Irish Rights Watch evidence to the British and Irish governments; check out the evidence that the British security state also ran the Republicans’ own internal security system.

Check out Martin Ingram’s book Stakeknife. Stakeknife is the code name for Fred Scappaticci — more stories will be emerging this year of his terrifying role as the architect of spectacular brutality, on behalf of Britain’s security services.

That was Adams’ world. That was everybody’s world actually, a world in which no nationalist or republican could conceivably take their troubles to the police — the RUC — they just couldn’t and didn’t.

That was Adams’ world. That was everybody’s world actually, a world in which no nationalist or republican could conceivably take their troubles to the police — the RUC — they just couldn’t and didn’t.

There was no hope of justice for women or children in those communities.

In Britain we aren’t in a war zone, and 90 per cent of us still don’t take our experience of rape or child sexual abuse to the police.

In Northern Ireland the police and criminal justice system was not safe for 100 per cent of women and children.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Republicans began to organise alternatives to the police and to the informal horrors of rough justice: punishment beatings. They set up restorative justice schemes and enlisted independent mediators.

But they knew — and I talked to them about this at the time — that restorative justice was not an appropriate mechanism for men’s intimate sexual oppression, abuse and domestic violence.

Femimists in the Republican movement were involved in trying to sort that stuff out. But they were all struggling in a war zone.

Since then, the narrative of republicanism and justice has been scalded by a new one: schisms within republicanism, particularly between those who supported the peace process and those who didn’t, intrudes upon the bitter bequest of abuse. Adams, inevitably got caught in that cross-fire.

An Irish friend reminds me that the absence of trust in systems of law and order during anti-colonial and civil wars is nothing new.

“It means that parallel systems of enforcing law and order emerge with typically bizarre sanctions and remedies.

“This happened between 1916 and 1922 in Ireland when Republican Courts meted out justice. This was even included in the film ‘The Wind that Shakes the Barley.’

“Some people forget this historical fact and choose to think that the more recent Republican incarnations of local ‘justice’ were an outrage.

“The RUC during the troubles did not deal with domestic violence, abuse or rape cases. They would not go to houses during the Troubles. People went to Republicans to seek justice or remedy.

“The way accusations or facts of rape were dealt with within Republican environments were extra-state.

“Living in an environment were the state is illegitimate is very frightening. This is the context within which we have to think about this.”

We are not entitled to bring British piety to an Adams family tragedy.

We could, though, learn something useful from Adams’ difficulties, and his survival.

We know that child sexual abuse is dangerous. People like Gerry Adams, were trying to confront it, sort it, cope with it, trying to get it right but doomed to get it wrong.

Uniquely in Europe, Ireland is well-educated about child sexual abuse. It is a culture in which Adams, who was not the problem, could be part of the solution.